TONY GARIFALAKIS THE NATIONAL: NEW AUSTRALIAN ART, MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART AUSTRALIA

29 March to 23 June 2019

'Tony Garifalakis' by Macushla Robinson

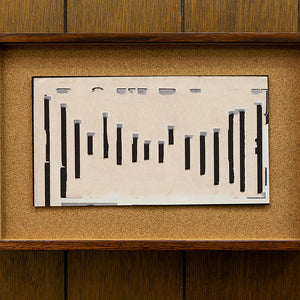

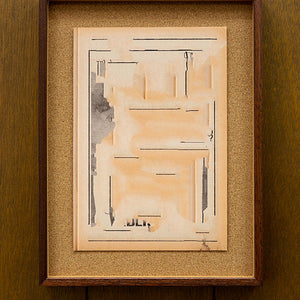

In my grandmother’s house there was a corkboard to which she affixed photographs. She never took any of them down, and gradually the board became a crowded collage of decades past – old girlfriends, new jobs, graduations, weddings, family vacations and dated haircuts. As time went on, the cyan and yellow pigments faded from many of the photographs, leaving only the magenta hue of analogue memory. When taken down, all that remained was an abstract pattern of pale overlapping rectangles, each marking the place of a now-absent image.

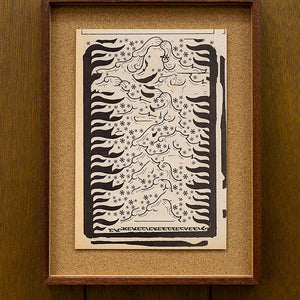

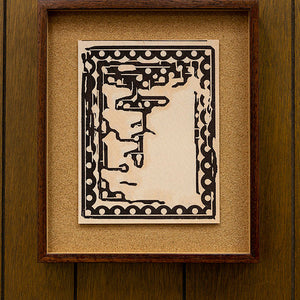

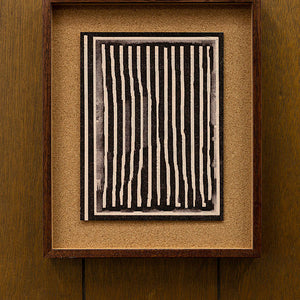

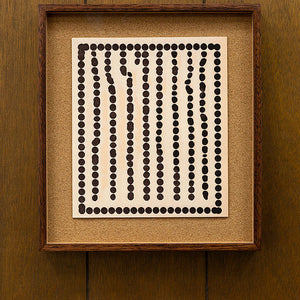

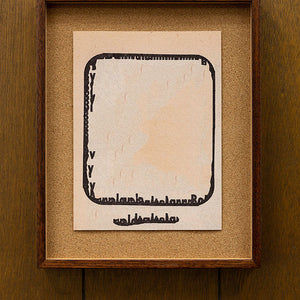

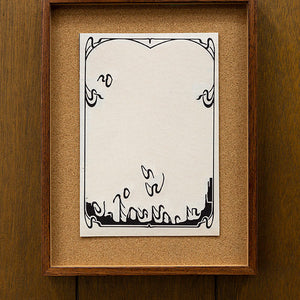

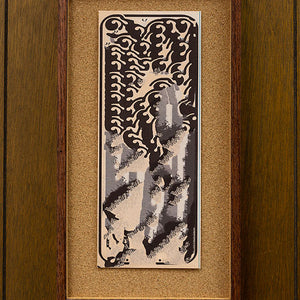

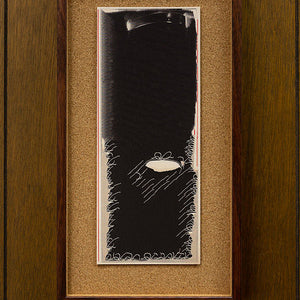

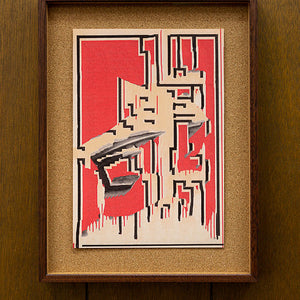

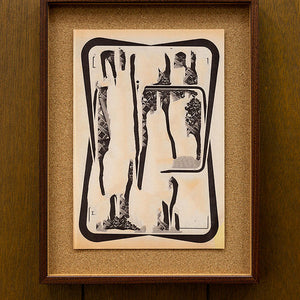

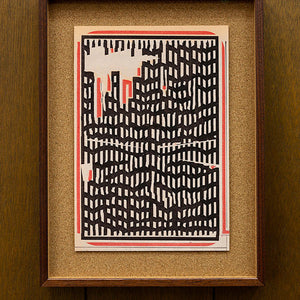

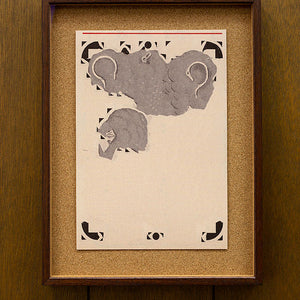

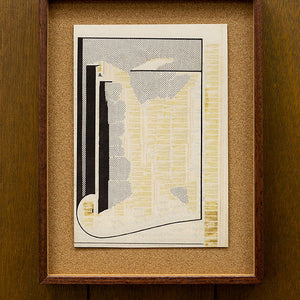

A series of abstract images, float-mounted on corkboard, hang on a timber veneer wall. You wouldn’t know it by looking at them, but they were born out of the pages of POMANTƩO (Romantso), a Greek romance magazine popular in the 1970s. We buy magazines for pleasure and consume them in idle time. We put them in stacks in the corners of our houses. They are not highly prized collectibles and neither are they entirely disposable. These particular magazines were written in the Greek language and read in Australia, and as such they represent both an unattainable fantasy and a comforting, familiar consumable. I imagine someone reading them in a living room panelled with timber veneer, thick carpet you can still smell, a boxy television and an orange lampshade. The home, like the magazines, would be at once aspirational and comfortable.

When writing his great unfinished work, The Arcades Project, Walter Benjamin picked through the detritus of history. He collected and indexed the forgotten, minor and lesser-known printed matter that was neither jettisoned nor enshrined in the historical canon, but which told the stories of our lives, the shape of our everyday. There is something of that historical thriftiness in Garifalakis’ work: his material is the stuff we left in a cardboard box in the garage, stuff we forgot about but are strangely delighted to find again.

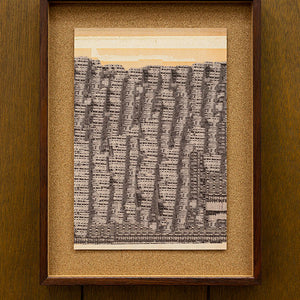

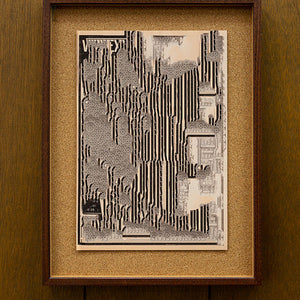

The pages of the magazine, a soft-focus collective imaginary, are unrecognisable now; they have been transformed into a series of dots and lines, abstract inky marks on cream paper. They are tantalisingly familiar but just beyond recognition. They could be landscapes, the pattern on an old and well-loved dress or the remnants of an art-deco poster on someone’s bedroom wall.

Their transformation is the product of digitisation. With a click of the cursor, the artist converts each image into a pattern that bears little resemblance to its source. It is a random act of translation (but also the product of the artist’s judicious selection). You could not reconstruct the original from these patterns; this is a one- way street that renders the past inaccessible but nevertheless reflects its tonal range, leaving a trace of its warmth and texture.