Artist Statement

Stories of metamorphosis and hybridity, the bastions of the monstrous, have permeated my work in various ways for many years. I am fascinated by the notion of transformation and that critical point at which a bodily change takes place and a new hybrid form arises, suspended between states. From werewolves splitting open their human shells and selkies shedding their wet skins, to Scylla the beautiful nymph of Greek Mythology morphing into a multi-appendage beast cursed with insatiable appetite, stories of transformation are rife with lurid descriptions. I try to locate my work at that point where a description will not suffice; the point where a being – or an idea – is arrested mid change and a new entity materialises.

Marina Warner’s writings on metamorphosis as a dynamic form of creation embodying processes of generation, growth and decay have been most influential. She identifies the taxonomy of transformation as hatching, mutating, splitting and doubling, the latter three of which are of most interest and relevance to my current work.

The new work, Beatrice, expands on ideas of the natural and the unnatural through signifiers of splicing, mutating, doubling and decaying and responds to a short story (discussed below) that for me embodies many of these concerns and examines ideas of the monstrous.

Beatrice has much in common with works developed recently for The National and utilises fabric manipulation techniques such as slashing, pinking and slitting which draw attention to the exposed interiors of the works. Crucially though, it is the location of the work at The Museum of Economic Botany in the Adelaide Botanic Gardens that provides an exciting new perspective.

In addition to Leigh’s curatorial premise and with this context in mind, the work responds to the short story Rappaccini’s Daughter (1844) by Nathanial Hawthorne; a story that captivated me at once with its elegant blend of Gothic narrative and perverse science in an exotic garden setting.

To summarise, the story concerns the fate of Beatrice, the human sister of the poisonous purple flowers her scientist father grows. Like the plant she is twinned with, the unfortunate Beatrice is the embodiment of poison – part maiden, part flower, all toxin. She longs to be loved but is all too aware that the touch of her hand leaves a painful mark and her breath kills insects and withers flowers.

Beatrice is analogous to the lethal plants that populate the garden, her home. She is a living, breathing instrument of poison; the human incarnation of her father’s barbaric botanical experiments described in the text as adulterous, monstrous and depraved. She, and only she, can tend her poisonous sister, whose perfume to her “is as the breath of life.”

As progenitor of both Beatrice and the toxic garden, Rappaccini is clearly the more ‘monstrous’ as he mocks the natural order of things, callously tormenting his daughter and her would-be lover, Giovanni, by luring him into the experiment. For his own part, Giovanni is both enthralled and repelled by Beatrice’s qualities, finding himself overwhelmed with “a wild offspring of both love and horror” as he is drawn first into her garden and then into her lethal embrace.

This text speaks to the notion of the monster as a conduit for fear and desire as well as the history of the ‘dangerous woman’ in literature. As Marina Warner notes, the dangerous woman – a Siren, a Lilith or a Gorgon for example – needs to be controlled, contained and dispatched by the plot. In this sense Beatrice is no different. Set apart from society and denied human contact due to her father’s so-called “marvellous gifts”, she is considered a dangerous creature that must be terminated before it has “perpetuated [itself]”.

In true Gothic style the story ends in tragedy when Beatrice, mortified that she has inadvertently infected Giovanni, drinks a ‘healing’ potion which is revealed to be an antidote to poison. As the very embodiment of poison herself, she is immediately annulled and drops dead.

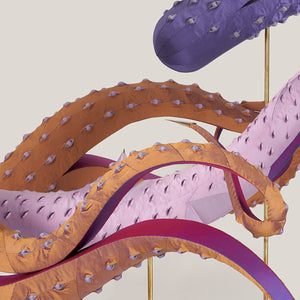

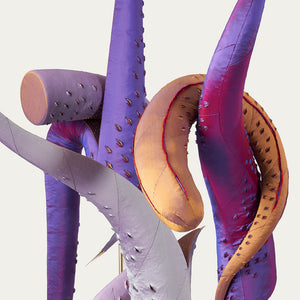

The work for the Biennial is a manifestation of Beatrice; an installation comprising multiple twisting, hybrid forms that project upwards on metal rods, mimicking the fatal flower garden that both imprisons and nourishes her. The work eschews any figurative human elements, presenting rather a metamorphic vision of Beatrice; a congress of body and plant, poison and beauty. Her ‘monstrous’ figure is signified by elaborately textured splitting, doubling and mutating plant-like forms and a palette of deep, rich purples paired with coppery browns.

The surrounding cabinets of fruit, fungus, seeds, skins and shells gives context to my manifestation of Beatrice. However, in a satisfying inversion of the function of a museum collection, the work will defy categorisation, aligning itself just as readily to monsters of Classical Mythology. The plant-like forms that comprise the installation are a deliberate nod to Scylla’s hideously tentacled lower body and depictions of mermaids with bifurcated tails. Positioned amongst the vegetal specimens of the Museum’s collection, alongside Monk’s Hood and Belladonna, Beatrice is a conflation of silken skins, spilled interiors and split forms that echo both bodies and fruit.