GARAWAN WANAMBI THE CLEANSING

6 October to 6 November 2021

'The Cleansing' by Will Stubbs

Arnhem Land is a big place. Because it is remote and still Aboriginal land, most people have trouble visualising what kind of place this is.

Europeans settled in the parts of the country that most closely matched their experience and living systems. The whole of Northern Australia is like a different country to the urbanised temperate south.

Within Arnhem Land there are a few big geographical features that stand out – the escarpment in the west near Kakadu; the Arafura Swamp, the largest wooded wetland in Australia; and Arnhem Bay, the subject of this exhibition.

If you look on a map, it is likely that Arnhem Bay will be one of the few features named in Arnhem Land. There is a simple reason for this. It is massive!

As an indication of its size, if you stand on the beach and look out into the bay, it appears that you are looking at the open sea. Although it is an impoundment, the opposite shore is invisible.

On the western side of Arnhem Bay is a place called Raymangirr, which belongs to the Marraŋu clan. It is a sacred and restricted area where fresh water springs to the surface of the beach in an area only exposed at low tide.

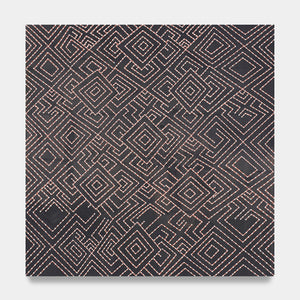

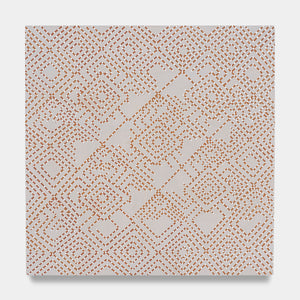

In special ceremonies dedicated to this clan and place, a larrakitj (a termite-hollowed, intricately painted tree trunk which acts as a memorial pole) is placed over the mouth of this spring at low tide and the water from this sacred font bubbles up over the top.

This is a symbolic cleansing of the land and people. A release of social tension caused by festering dispute. A living manifestation of the ecstatic peace of harmonious justice.

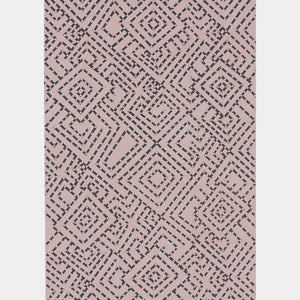

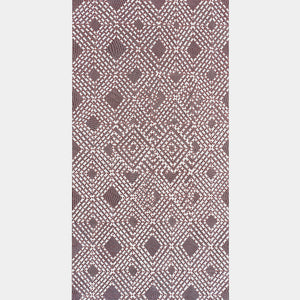

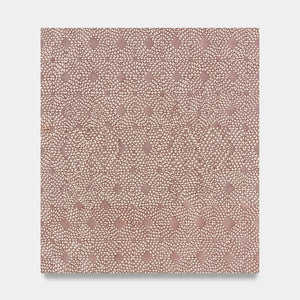

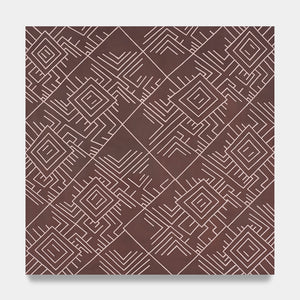

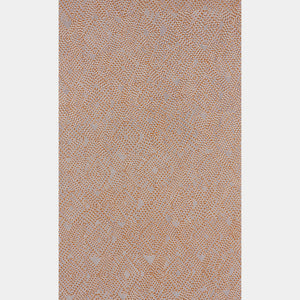

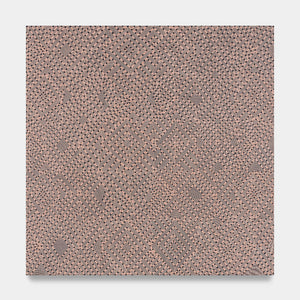

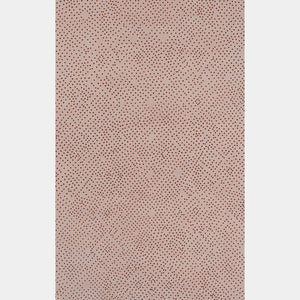

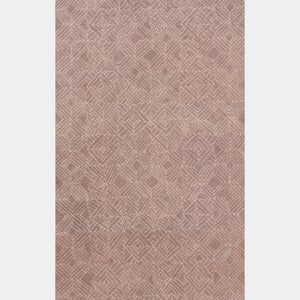

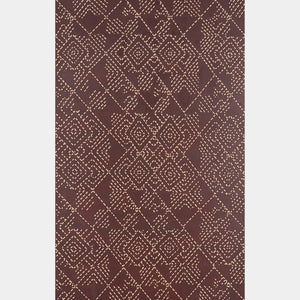

To understand the imagery in Garawan Waṉambi’s exhibition, it helps to see through Yolŋu glasses. When Yolŋu look at the world, they see all of its component parts decorated in a specific clan design. A way for us to understand this is to think of a supermarket made up of thousands of separate items but with discrete brands. The design belonging to each brand may spread over a number of different products. Also, a wide range of similar items could be wearing the livery of a huge number of different brands. When you know the brands, you can see from a distance which brand of olive oil is which.

The whole together makes a glittering kaleidoscopic tapestry of meaning. We have a feeling of richness and plenty in the panoply of identities signalling us frenetically. And this is how the bush communicates to Yolŋu. They don’t just see a pheasant coucal – with their special vision, they can see that it is wearing the patterns of the Galpu clan. And this X-ray vision applies not just to every bird, plant and animal species but also to people and places. Maybe try to imagine for a minute the way that Yolŋu walking through the bush are inundated with these cryptic patterns.

And so it is at Raymangirr. The land and the sea of this coastal beach is stamped with the pattern that you can see in Garawan’s work. And the larrakitj placed over that spring is physically painted with that pattern, which even we can see. But when you slip your Yolŋu glasses on, suddenly the painting on the pole is set against a backdrop of the hidden pattern in the landscape itself. This resonation between the pattern on the pole and the pattern it is set against is the key to what is happening in these works to one degree or another. It is why our eye gets lost, where the dimensions seem to warp and meld.