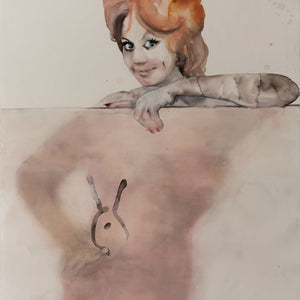

FIONA MCMONAGLE THAT'S BUNNY

3 February to 5 March 2022

That's Bunny

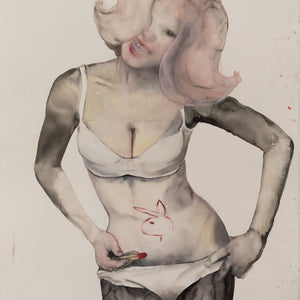

The rabbit, the bunny, in America has a sexual meaning; and I chose it because it's a fresh animal, shy, vivacious, jumping - sexy. First it smells you then it escapes, then it comes back, and you feel like caressing it, playing with it. A girl resembles a bunny. Joyful, joking. Consider the girl we made popular: the Playmate of the Month. She is never sophisticated, a girl you cannot really have. She is a young, healthy, simple girl - the girl next door ... we are not interested in the mysterious, difficult woman, the femme fatale, who wears elegant underwear, with lace, and she is sad, and somehow mentally filthy. The Playboy girl has no lace, no underwear, she is naked, well washed with soap and water, and she is happy. - Hugh Heffner, founder of Playboy

The objectification of women across mainstream media has a long and tainted history. Detractors, however, tend to frame such an analysis as an exaggeration, which they dismiss along with most feminist critiques of society. For some time now McMonagle has focussed on the portrayal of women within popular culture. In previous series such as Titled and Smoke and Mirrors she has been working to counteract the various and conspicuous ways these images enter and filter through society and how this impacts each generation. In her latest body of work, That’s Bunny, McMonagle shifts her focus to the sexual exploitation and objectification of women in what are traditionally known as “men’s magazines”, and specifically Playboy with its gratuitous tagline “entertainment for men”. Renown, for its Rabbit logo and centrefolds of nude and semi-nude models, Playboy remains one of the world's most familiar brands.

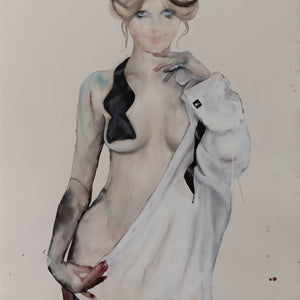

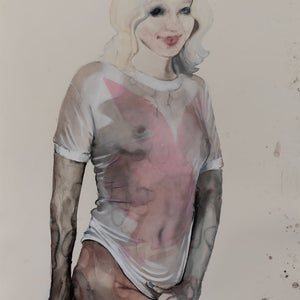

Drawing upon her observations McMonagle’s paintings ask; What is femininity? How is it measured? What are its demands? How are women meant to dress, look, think, act, feel, and be, according to the mores of society and / or media? Frequently besieged with distorted male perspectives, trivialised, marginalised. And as these new works question, transformed into "the bunny". In addressing these questions McMonagle offers a witty and often pointed critique of the concept of femininity in contemporary culture and throughout history.

From earlier series that articulate suburban life and character, McMonagle’s portraits have turned a searing and intimate eye upon the domestic and private life of the working to middle classes. Though often evocative of a specific Australian lifestyle, through her deft use of watercolour the audience have been able to enter many kinds of living rooms, bedrooms and backyards. It is not surprising then, that McMonagle has continued to mine her personal history to discern the conflicts and tensions between femininity and feminism; as she says “to help us understand that space that allows women to be comfortable in all their wonder regardless of age, role or culture; a space independent to the male perspective".

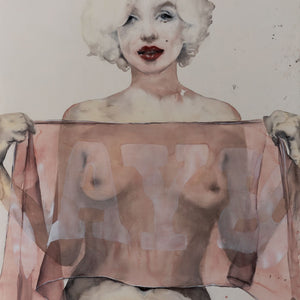

Describing the inhumanity of trying to look a part that does not exist, author and feminist Susan Brownmiller refers to a woman’s quest for self-love and acceptance as “obsessive concentration”. Turning a scrutinizing gaze on the images to which women have become either conditioned or pressured to respond to, in an inverted ‘turn of the screw’ McMonagle’s act of painting mediates such “obsessive concentration”. Translated in the space of the studio and the eye of the female critic these images are sent back into the public sphere drastically altered. Through McMonagle’s deployment of watercolour, one which carefully exploits the fragile vulnerability of the medium the “ideal image of womanhood” begins to wobble. The image / the ideal tremors, it cries, it slaps back, it starts to speak a different language. The iconic Marilyn Monroe lip flutter is no longer a sexual invitation, it is Norma Jeane Mortenson trembling on a precipice. On the edge of fame, of public life over any hope of privacy, of sexualised icon before female character. It is womanhood confronted and affronted.

Monroe is the only recognizable ‘portrait’ in That’s Bunny, and this is McMonagle’s subtle way of addressing the source material. Founded in 1953 it was Monroe’s image that launched the multi-million dollar empire and magazine and Hefner always attributed the success of Playboy to Monroe’s inclusion in its inaugural issue. But Monroe never signed an agreement to be in Playboy nor was she ever financially renumerated for the images that were published. Heffner acquired nude pictures from a photographer Norma Jeane had posed for when she was a financially struggling young actress. It must be acknowledged that from its inception Playboy has flourished on the compromised female image.

Aside from A Cover Up, That’s Bunny is not about “identifying” the females that are rearticulated in the work. These are iconic mainstream images - the woman in the champagne glass, behind the misted shower screen, we cannot identify them perse (persona). Instead “they ring a bell”, they awaken us to a dormant remembering, and the longer we look at the image, the wobble, the tremor, the cry grows stronger: “this is not one woman it is all women”.

McMonagle’s women are not one dimensional, they are complex humans. What Hefner and Playboy, much of the popular culture, that McMonagle dissects never did was present women as human. Hefner simply made the discriminatory equation of the female sex as sex object more accessible and prevalent: the Playboy centrefold is the girl next door, not the famous unreachable movie actress. This is in no way a democratization of woman, rather a downward shift that broadens the triumvirate male gaze of female, sex and object. The casualness of the Playboy model gave licence for men to look at all women in this way and not to pretend otherwise.

As McMonagle observes “we grew up with these images on the supermarket shelves – that was just what we were raised on”. And this is what her images address – the casualised erotic forms through which we regard the female sex, female actress, the young pop star, the baseball and tennis players, the student in science class, the librarian. The list goes on, yet for each of these roles we can easily summon up in our mind’s eye a hyperreal sexualised version of any these everyday human roles. McMonagle’s images oppose this. Here are women who bleed, wear elegant lingerie with lace, are sad. They are those women cast as femme fatales when their relationships break down. They break down. That’s life. It is mentally filthy. That is humanity in all its sticky and slippery form. It is all the stuff that Heffner, wanted to ignore. McMonagle’s women have many stories to tell, what she asks through her images is to recognise the fallacious fantasy, the objectifying gaze, and the capacity of art to pose these questions while not denying its contribution to the aestheticization of the female figure.

Written by Sangeeta Sandrasegar, 2022