THE NATIONAL: NEW AUSTRALIAN ART, MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART AUSTRALIA, 2019

2019

'Julia Robinson' by Jenna McKenzie, 2019

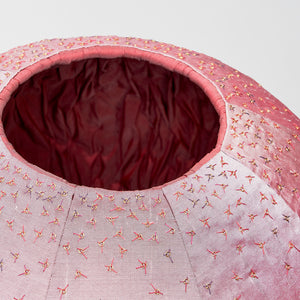

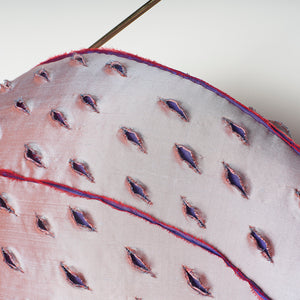

Cold, dusty skin swells, ballooning outwards from the perfectly round aperture of a gourd. Tongue or tendril, shoot or sprig, a shock of blue-smocked fabric emanates from an amniotic abyss. Coiled and wrapped, clothed and dressed, silks the shade of a tender bruise adorn the fantastical forms of Julia Robinson’s new work. These otherworldly objects emerge from the suspended animation of their wall fittings. An exotic banquet of surfaces is offered to the viewer, ranging from perfectly smooth metals (polished brass, steel and gold) and intricately smocked, slashed or jack- plated silks, to the raw, untreated surface of the gourds. Together, they mutate, hatch, split and pierce, invoking the transitional state of metamorphosis.

Exploration of transformative states is an intrinsic part of the Adelaide-based artist’s practice. Robinson, who works in the fields of sculpture and installation, has an enduring fascination with sex and death. Drawing on a multitude of sources including myth, superstition, folklore and calendric celebrations rooted in the changing of the seasons, her work reflects an interest in how humans address existence and mortality through ritual.

Robinson introduced gourds into her work in 2016 with The Song of Master John Goodfellow. These symbols of fecundity erupted into her practice with bawdy ebullience, referencing ceremonial vestments and the intricate techniques of Elizabethan-era clothing. In Long Ballads (2017), Robinson extended her investigations into the realm of adornment and early-modern costuming with a sensitively executed collection of gourd-based works. For The National 2019 Robinson returns to this fertility motif – slicing, dressing, piercing and gold plating the gourd, traversing the dichotomies of interior and exterior. She describes this new body of work as ‘a dialogue with Hieronymus Bosch about ritual, growth and fecundity by way of his remarkable painting The Garden of Earthly Delights (c.1504)’. (1)

For Robinson, Bosch’s garden is alive with the processes of fertilisation, germination and ripening. In his hands, the Garden of Eden becomes a site for metamorphoses, redolent with the mutating, hatching, splitting (2) of the plant world. The central panel of Bosch’s biologically and metaphorically charged painting became a touchstone for this new body of work, with key compositional elements of the painting finding their way into sculptural forms. Thus, a hoop holding a human figure is echoed in the warty loop of a gold-dipped gourd, and the form of a fleshy turret appears, pierced by a brass spike. At the centre of Bosch’s painting, groups of feverish revellers recall the merrymaking of May Day and spring rites. Yet this celebratory place also contains the seeds of sin and damnation. Robinson artfully picks up and extends the atmosphere and contradictory forces at play in Bosch’s garden. Exposure is counterpointed by enclosure; the sanctity of skin and surface is disrupted and pierced; principles of order (culture) and disorder (chaos) are complicated.

Through the act of dressing, Robinson not only applies all the trappings of culture to these objects, she enacts a kind of transformation. Here, the artist becomes transmuter of observation, intuition and urge, mobilised to create new physical forms. Exquisitely finished surfaces, at once familiar and strange, reveal the subtle elements and tensions of a world in flux. In Robinson’s hands, these objects are emissaries of metamorphosis itself. Emerging from a constant state of becoming, they crystallise that which sits on the edge of conscious awareness.

Notes

(1) Interview between the artist and author, June 2018.

(2) See Marina Warner, Fantastic Metamorphoses, Other Worlds: Ways of Telling the Self, Oxford University Press, 2004, pp.29–160: Warner uses the terms ‘mutating’, ‘hatching’ and ‘splitting’ as organising principles to explore the notion of metamorphosis. For Warner, metamorphosis is a dynamic process that belongs to the natural world, yet it also threatens our sense of fixedness.

—

This project has been assisted by the South Australian Government through Arts South Australia and the by Australian Government through the Australia Council for the Arts, its arts funding and advisory body.