SETTLEMENT AND THE GATEKEEPERS

12 November to 9 December 2020

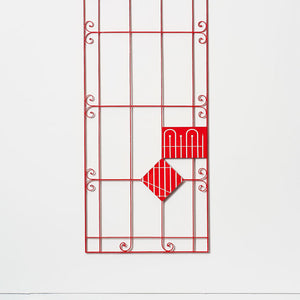

'everyone works but the vacant lot’ by Melinda Rackham

A voyeur of sorts, Elvis Richardson savours the intimacies of others, collecting and curating imagery from public repositories to explore emotionally and politically charged narratives.

Previously she has purchased discarded family collections of 35mm transparency slides on Ebay to re-exhibit as the ongoing archive Slide Show Land (2001 -) and recast YouTube videos of hopeful young girls singing the optimistic orphans’ ballad Tomorrow (2006) from the Broadway musical Annie. Now in Settlement (2015-16), interior photographs of houses from the low end of Domain.com.au are reposted to Facebook, creating a reflexive moment amongst the chatter of cat videos, vacation selfies and status updates.

Selected via For Sale search criteria results for “2 bedroom house“ “less than $250,000” “anywhere in Australia”, these flat, low resolution, mostly amateur images are surprisingly powerful. Posted over an 18-month period without comment, they elicited a range of responses from nostalgia for childhood familiarity, humour with a touch of moral judgement; empathy for the embedded tragedy; to tenancy enquiries and critiques of disruption and movement in late neoliberal capitalism.

Littered with ornament and wood veneer, these rooms could be posited as humorous, as other, as kitsch. A cacophony of mismatched furniture echoes psychosis inducing texture and pattern, however Richardson’s astute curation places the found imagery of Settlement’s second iteration – a nine minute HD Video with sound by James Hayes and A3 magazine, as the traces of lives ordinarily lived.

Povera is on display. A laziness of socks, the pathology of too many clocks, blinds drawn in secrecy, ugly moments, Elvis memorabilia, cubist heaters and aircon ducts. Formalism thinly masks socioeconomic reality. A red chair lounges, gazing towards frosted windows in a sunroom without a view; oddly placed power points float, cream clouds on powder blue asbestos walls; a ray of sunlight quivers across the pink quilted flammable bedspread.

These houses are undressed, unbeautiful, superseded – shocking to us as sophisticated consumers of the style industry. They have slipped through the gaps of renovation and design, unadorned by granite bench tops, Italian mosaic tiles, stainless steel appliances, marble bathrooms. Failures in the revolving door of fashion. Losers in the investment market.

We glimpse the tropes of suburban horror and true crime in Settlement. A doll upon a single bed stares squarely at itself in the mirror, ominous nicotine yellowed cupboards sit below a ceiling manhole cover, slightly ajar. Eyes widen as we spot pets nestled in grotesque fleshy pink and rancid green soft furnishing; a casual axe rests amongst a sea of grey home office document boxes; a conspicuously stuffed body sized bag creeps into an overfull room.

Yet this horror is the ordinary horror of everyday poverty in Australian homes – the underpaid, the not paid, the badly resourced, the regional, the young, the ageing; a growing underclass of artists and writers. The crime is the unaffordability of the ‘Australian Dream’ of home ownership. Compared to European standards our bloated Australian property market provides no alternative but a scarcity of permanency and security for renters.

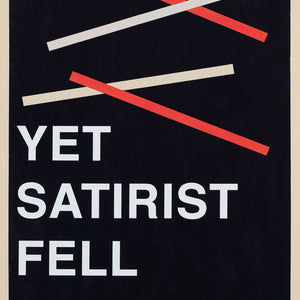

Inspired by the tag ‘everyone works but the vacant lot’ from 19th Century American political economist and philosopher Henry George, Richardson has researched the particular inequities of the Australian Housing Sector for a decade. Imagine if we employed Georgist reform philosophies where land, resource and rents are shared for common good in lieu of taxes, intellectual property is abolished, public transport is free and there is a universal pension. It is economically possible.

Yet what we have are remnants of displaced lives, the itinerant, those without secure groundings, the hastily departed, the abandoned, those of questionable identity. Forlorn pictures, once precious, packed, stacked, ready to go. Forgotten encyclopaedias, traumatic divorces, a conversation of chairs, multiple singular beds. The sweaty indent of a sleeper’s head on a stained pillow. Exquisite? Sublime? Mundane?

And then there is the deceased estate. Posted on August 28, 2015, Richardson’s final noir video segment and the cover of the magazine, shows a candle lit framed photograph of a femme fatale from another era upon a substantial fireplace. Focus pulls back to her empty hospital bed in a distant room, with a lifetime of things now packed to be recycled to family, friends and charity shops.

Presence in absence has been a powerful anchor of Richardson’s practice for two decades. Understatement allows the viewer to construct his or her own narrative from what may at first appear to be unremarkable. In Home (1996) she displayed 100 square meters of ‘Trophy’ grey carpet removed from a youth refuge in the window in Sydney District Criminal Court. The same year saw her iconic work, Found Paints Land, a reprinted found Polaroid of a white bikini clad woman posed in front of a black mini beside a sandy beach track.

In the same vein Settlement’s interiors are both personally and socioeconomically reflective. They document the dilemma of the artist; the place of home in our national psyche; and the affect of lives in transition. Usually we settle with an economic transaction, however Richardson disrupts the intent of real estate marketing. Settlement’s deeply layered narratives offer the choice to settle for a vacant lot, or resettle it for our own ends.

October, 2016