'Believe It or Not | Very Superstitious' by Amita Kirpalani

When you believe in things that you don’t understand,

Then you suffer,

Superstition ain’t the way

Very superstitious, wash your face and hands,

Rid me of the problem, do all that you can,

Keep me in a daydream, keep me goin’ strong,

You don’t wanna save me, sad is my song

– Stevie Wonder

Superstition, as represented in this new series of work by Richard Lewer, is imagined as a rich seam of evidence and storytelling that challenges logic. As Stevie Wonder warns us, “Superstition ain’t the way”. Superstition can be allied with obsessive and compulsive acts. The recurring thought (an obsession) causes pre-occupation, and an irresistible urge (a compulsion) – either mental or physical, sometimes against one’s conscious wishes. For the obsessive and the compulsive parts of us, an extraordinary external threat can be solved by the most ordinary of actions: An extreme example might be preventing sudden death through turning a light switch on and off multiple times; a less extreme example might be wearing a ‘lucky’ hat. Maybe this system is also true of art-making and writing. Circumstances must be ‘correct’ (whatever ‘correct’ is, e.g. light switch on or off, wearing lucky hat) in order for creativity to kick in. The relationship between rituals and magical thinking is a universal experience, and a source of suffering and anxiety: a fear of harm in the form of ‘bad luck’ and misfortune. Rituals, ceremonies, and compulsions – personal and collective – are the ‘doing’ of superstition and magical thinking.

Lewer’s ‘doing’ is through layering the painted surface and removing it, time and time again until the surface settles into a place where he can proceed. This is also a kind of anxious magic. For him, there is a special time and place where these rituals must occur (the studio) and a complex precision in search of an unfixed and highly idiosyncratic version of ‘correct’.

Vortexes

The familiar story of Picnic at Hanging Rock (a film based on a 1967 novel) is about the disappearance of a group of school girls and their teacher at Hanging Rock, Victoria on Valentines Day in 1900. As Lewer indicates in the work The Pact, the fiction continues to haunt the landscape.

The Pact contains a surface that is dotted with white marks, splotches and daubs of paint. These breaks in the darkness become pathways of understanding, clues, hints and troubling instances of inaccuracy. Lewer’s deliberate ‘undoing’ of the dark surface is the interweaving of truth and fiction, both so often indistinguishable. The schoolgirls rendered here are less beacons of innocence in white-flowing dresses, and more Macbeth-like white witches, each haggard with toil and trouble in their ghostliness. Lewer’s ring-a-rosie of ‘white witches’ form a vortex or portal and speak not to the film or novel but directly to the Hanging Rock area as a sacred place of Wurundjeri male initiation ceremonies: This place of innocence and transformation reverberates around the painted surface. The Wurundjeri were dispossessed of this land in 1844 and Lewer yokes the ‘unstable’ painted surface with the ‘unsettled’ landscape.

Shapeshifting is an important part of mythmaking where the layering of fictions becomes the perfect setting for new sightings, new witnesses and new evidence to be uncovered. This type of transformation is again witnessed in The headless wanderer which depicts the story of an Aboriginal woman named Biddy, a slave for sealers in the Wilsons Promontory area, who was eventually murdered by decapitation. It is possible to walk down “Biddy’s Track”, a marked trail through dense bush, where there have been alleged sightings of Biddy’s ghost. Lewer’s interest in and fascination with mothers, female saints and women elders follows their role as caregivers and key storytellers.

The physical torment that supplication or servitude to faith anchors the unreal in the body. The paintings, The Crucifiction, Saint Mary Mackillop and Servant of God Therese Neumann are symbolic of the miracle: an instance where humanity exceeds expectation, contravening both natural and scientific law. Perhaps miracles too are a kind of light in the dark, an event or instance of hopefulness in the fug of everyday life. These three paintings point to the failure of the human body, of commonplace illness and misfortune, and persecution and a radical transformation. A convergence of the supernatural and religious, the Saint (Mary Mackillop) and the mystic (Therese Neumann) are revered and canonised, their portraits searched for meaning by believers over lifetimes.

The seen unseen

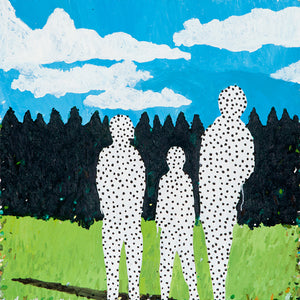

The couple in Together forever, and the three missing Beaumont children in Gone without a trace, operate as portraits of the seen-unseen.

Together forever describes the tragic devotion of Mr and Mrs Crawley, whose ghosts haunt a regional Victorian house called Monte Christo. After Mr Crawley died it was said that Mrs Crawley left the house only twice in 23 years. Here a posed portrait, not dissimilar to the paintings of the couple that are hung in the house, has become emptied, possibly of fact and of a true likeness.

Like a body of evidence that has become muddied over time, these actual crimes become ghost stories. So many violent crimes manifest like this, the detail in the retelling becoming necessarily warped, too difficult to recount, and the story itself an outline sitting within the landscape, like a fog or a chalk outline.

The black embodied shadow in Yowie is also representative truth diluted. A potentially real story of an actual sighting of something, perhaps human, or perhaps animal, becomes distorted and the fiction becomes trapped in a landscape, forever running from further evidence.

Stars

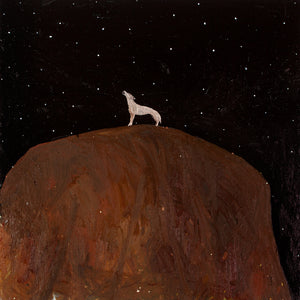

‘Operation Ochre’ was the name of the Northern Territory police taskforce that in 1981 was formed to further research the mysterious disappearance of Azaria Chamberlain. The taskforce, named after the red desert of Uluru, adopted a cartoon logo of a dingo. The actual dingo in question was spared the trial-by-media that Azaria’s mother, Lindy Chamberlain endured, and Lewer’s painting reminds us of this. The setting – on sacred Aboriginal land – for this mystery (solved and resolved in the 30 years since) has been variously described as a place of bad luck and eeriness. In the same holiday, the Chamberlain family visited the Devil’s Marbles near Alice Springs and an ominous place called Cut Throat Cave, as well as the Fertility Cave at the base of Uluru.

Lindy’s outfits, demeanor and speech became a focus for journalistic enquiry: an alternative way of accruing evidence in order to solve the mystery. A religious woman, she suggested several times that there was divine purpose in the Azaria case, and that its purpose was to “bring people back to God”. Lindy Chamberlain’s website has its own logo which carries the phrase “Only you can imprison your mind”. A strange choice perhaps, but this is all about endurance and misconception. Baying at the lonely night sky, the dingo in A Cry in the night is a haunting metaphorical last cry that reverberates around Australian folklore.

Flickers

Images and stories alike flicker in the mind: they return and are held there, sometimes because of triggers unknown. Lewer depicts this in the painting The Min Min lights. The Min Min Lights are unusual light formations found in both Aboriginal dreaming stories and in Australian folklore, explained by scientists as Fata Morgana, where the complex grid of vision becomes skewed and ‘visions’ or mirrors of objects appear. Just outside the town, in the 120km stretch of road, the Boula Shire has erected a sign that reads: “This unsolved modern mystery is a light that at times follows travellers for long distances – it has been approached but never identified”. First sighted in 1918, these lights supposedly compel drivers follow, only for the drivers to disappear. Also an instance of flickering lights, Westhall 66 describes the 1966 sighting of a UFO landing in a paddock near Westhall High School. Over 200 people saw the event and it has been variously explained and re-explained as nuclear testing, a high-altitude balloon, and secret government business. These flickers could be tricks of the eye, and Lewer is fascinated with the ways in which these stories compel us to search the landscape, waiting for something to emerge.

Bird’s eye

A link between life and death, Lewer depicts 5 crows or ravens in Impending Doom. The mythology of this carrion bird is rich with symbolism, where to see (the figure) 6 is a sign of impending death, and to see 5 is a sign of impending sickness. Like a naturally occurring tarot card, the raven’s call signals weakness, death and decay. In this painting Lewer’s landscape evokes a violent crescendo, where these birds look on at human folly, violence and bad faith.

Voids

Unseen forces underpin this series of work. To vanish or to be removed inexplicably, sometimes without a trace, forms the basis for The Ghost Train. It is said that the ghost of Emily Bollard, a woman who was taking a shortcut through the tunnel in Picton NSW in 1916, only to be greeted by an oncoming train, haunts the tunnel. The locomotive struck her and carried her mangled corpse in its cowcatcher all the way to the town’s railway station. According to local folklore, you can still encounter her ghost in the tunnel, forever trying to run from her oncoming doom. Lewer’s layering of this dark void disrupts, breaks and lingers, like superstition within logic.

Freckles

Lewer’s use of dots, holes, voids and gaps as part of his painting practice operates as a kind of coded self-portraiture. The marks morph, repeat and change form throughout this series of paintings, which we can read as Lewer’s compulsive act of situating the self in each work as storyteller: his need to understand and map. These circular marks on each canvas, rendered in either white or black are a crucial part of the artist’s visual language and conceptual logic and are symbolic of self. To be a red-headed child is to possess correspondingly colored freckles – both a highlight of a highlight, and a stigma.

Pockmarks, freckles, vortexes, holes, voids, gaps, stars, stigmata, gateways, portals and holes are metaphorical instances of logic: a piercing of a good or compelling story with fact. These spots, tears and breaks are also compulsive mark-making, the describing and re-describing of the inexplicable, perhaps to ward off the darkness.

Amita Kirpalani is a writer and curator based in Melbourne