'Unforeseen Phenomena' by Chris Abrahams

I was honoured to have been asked by Justine to write something about her most recent work. She had heard me perform with my group The Necks at Café Oto in London in 2014, and felt we shared a strong like-mindedness in our approaches to making art. With me not being particularly well versed in either historical or contemporary photographic practice, we decided I should write about what I know – my own work – and allow for the reader to draw his or her own conclusions as to the similarities it shares with Justine’s.

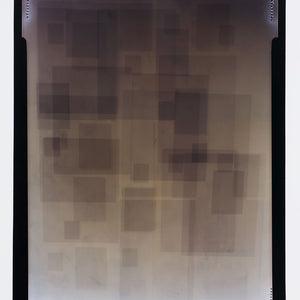

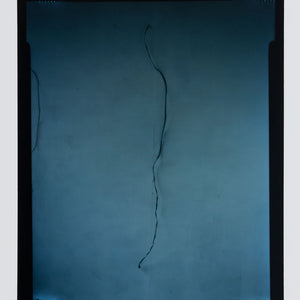

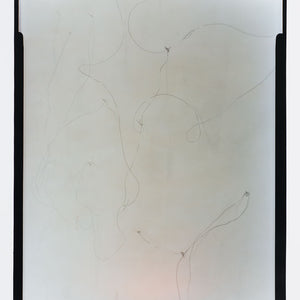

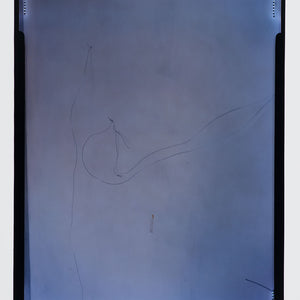

Certain similarities struck me right away. Foremost is the allowance for unforeseen phenomena to heavily influence both the construction processes and final outcomes of the photographs – whether these be the unknowing contact of the passersby; the influence of architectural elements; or the unpredictable lighting discrepancies found in a dark room. There is also the amassing of similar, discreet utterances – through multiple exposures (with each utterance a distinct performance) – to build up her pieces. In her exploration of the long exposure, time itself comes to the fore (time becomes Time), lending to Justine’s work a decided musicality. In the palimpsests behind the resultant images, lie months of shifting rhythms – haptic and light-based, social and natural, regular and chaotic.

The following, then, is an attempt to write, aphoristically, about some of my approaches to playing the piano and making recordings. One musicality is here being used to speak about the other.

*

Things can seem like they’re repeating but they’re not. Tiny discrepancies in each utterance can, over a sequence of utterances, lead to massive change – to the arrival at a place without knowledge of how that feat was accomplished. How did we get here? Nothing seemed to be changing and yet, here we are.

It’s a little like cellular division in the aging process. A piece goes from young to old, having a teleology that works against pure ambience. The smaller the discrepancies, the more covert is the development; also the more hypnotic. The discrepancies are unavoidable, not planned. They come about through human action – the non- repeatability of human action.

There must be the allowance of space for things to develop outside of the control of the performer/composer. The influence of light; of acoustics; of architectural space; the quality of tools and instruments; the emotional energy from people in the audience – all of these things influence how a piece develops in both formal and aesthetic ways. Things start to sound exciting; things begin to resonate and reflect off surfaces in strange ways. I naturally gravitate towards these things. I don’t verbalise or intellectualise – I don’t consciously decide. I just go with it – try to keep reproducing whatever it is that’s causing the phenomena to occur.

The elements that are out of the control of the performer are noise elements. Noise is not an autonomous thing, separate to a piece of music or work of art; It as an element that brings about distance between the artist and the resultant work. All human performances have a noise dimension to them, with some performances being noisier than others.

The work is site specific; no two spaces are exactly the same; no two instruments are the same; no two audiences are the same; no two amplification systems are the same.

In a sense, the music plays you. Something powerful starts to happen and one tries to keep it happening – tries not to consciously dictate where things go. I don’t want to hear myself making decisions. I want to make music. I don’t want to merely aestheticise my conscious thoughts.

It’s important to create something that can then direct itself. One produces the raw sound that feeds the music, but the music has a sentience of its own – an autonomy. One is compelled to keep providing the music with sound.

One must step outside of the composition and enjoy it as if a member of the audience. A feedback loop happens – the artist is informed by the work to make more of it.

The piece will complete itself in its own time.

I’m not interested in consciously trying to force the music into premeditated formal structures. To force it to conform to a structure would be detrimental to it, it will arrive with its own structure, if allowed. One thing follows another; that is the structure.

To strike the surface of the string repeatedly with a hammer, at a high frequency, results in unpredictable harmonic modulation. This is because the string is still vibrating when it is struck again and again – with each strike occurring at different stages of the string’s vibrating envelope.

There is a form of sonic animation at work. The harsh, individual attacks of the piano’s hammers hitting strings, join together to create a fluid, moving continuous sound, rather like film frames speeding in front of a projector’s light. The resonation of one string can cause other strings to vibrate sympathetically. The amount of sympathetic resonation is wildly different between instruments.

Pressing the piano keys down is an expressive act, not merely a delivery system for sound production. There is an emotional quality to the physical act.

Control of the piano hammer is relinquished prior to it hitting the string. In essence the hammer is thrown at the string – the last few millimetres of its transit are in free fall.

The hammer fall prints a vibration.

The outcome of the recording of a live performance is unknown – sometimes it’s predictable, sometimes it isn’t.

The reproduction – playing back – of a live recording is an approximation. Nothing but a replica of the pipes of an organ, for instance, can convey the quality of sound generated by the myriad of discreet sound producing elements of the instrument.

With a recording, the unfolding of a piece of music can be heard over and over again, with each listening signifying a different set of meanings to the listener. This is not limited to the specificity of the playback machinery or the domain of acoustics. Things that may have sounded exciting in the moment of performance can lose their vitality by being heard a second time – large shifts in dynamics can sound illogical or contrived once decoupled from an unfolding teleology.

Some things should only be listened to once – while they’re being made.

On the other hand, performances that may have seemed disappointing at the time of their creation can be deeply powerful when listened back to, on a recording.

The production of a recording generally sees an infinite number of acoustic perspectives reduced down to two – there is a change in dimensionality.

All energy is lost as heat. A vibrating piano string on its journey to stasis will spend its energy as heat.

*

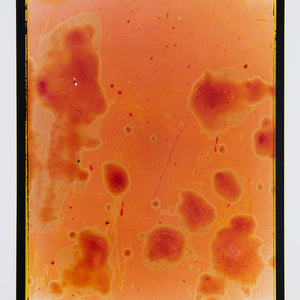

There are other musical/sound art approaches that seem related to Justine’s work. The use of analog field recordings is one. Justine’s “field recordings”, however, are made without the use of a device; they are akin to leaving the analog recording tape itself out in the open.

I’m also reminded of Ross Bolleter’s music, made on ruined pianos – these are instruments that have spent a required amount of time outdoors in order to be classified as “ruined”. However, Justine uses a camera as much to ruin images as to capture them.

Another thing that comes to mind is Steve Reich’s Pendulum Music – whereby a “feeding back” microphone is left to swing, suspended above a speaker cone through which it’s being amplified. Over time, with the gradual diminution of the arc of the swing, increasingly longer lasting bouts of feedback are brought about until finally stasis is reached and the microphone hangs directly above the speaker, feeding back continuously.

The similarity is in the allowance for the influence of unmitigated physics on the creation of the work. Justine’s photographs make me think about Noise and whether, once incorporated into a work of art, it can still exist as a thing in itself.

Apperception by Justine Varga

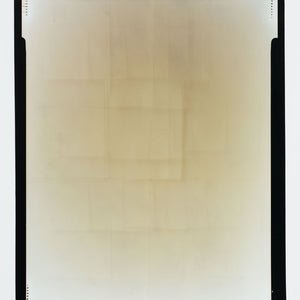

To expose a negative is to ruin it. From the moment it is exposed to light, that negative is spent. Before this moment, when it is still just a strip of infinite darkness, a negative is all potential. The photograph is most pure in this moment, crisp in its latency – untouched and unmarked, it is nothing but what it might yet become. It could contain each and every thought, any design imaginable. When I think about photography in these terms, I realise how limited I am compared to a photograph. I confront the fact that, in the very moment I expose a negative to light, it has already fallen from grace.

It is with the rupture of night (the failure of darkness, of the negative) that I recover the point of zero. In making the first mark – when I surrender to the making of it – there is no wrong. It is the source of freedom from which to make a photograph. I can begin. From here I fill the gap between each moment and action. It is from this in- between that I attempt to retrieve the past from the present – a shifting location I constantly return to.

Within stratums of shade I am concealed, unseen among the depths of layers. I depart in increments along a strip of time. It is a displacement by which I am two places at once – behind and in front of the camera – in the centre as well as at the edge. I am everywhere and nowhere at all. Underneath a canopy of night, I expand and contract to an infinite circle and the smallest square. Remember me as error, all the mistakes embraced: fingerprints, a smudge, the tone of heavy breathing.

When you arrive someplace new, you breathe in to relate it to the places you have been before. When you breathe out you begin to fill that new place with a mixture of here and there. Unknowingly, a transaction takes place between the two locations; between the self (the place you were before) and the room in which you find yourself standing. My photography is bit like this. It is a kind of respiration of light. Like a condensation on glass, it momentarily obscures my vision, before once again revealing a reflection re-doubled.

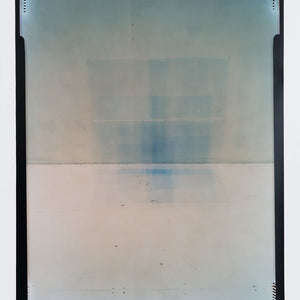

Slowly but surely absorbing the gentlest ambient light, my photography knowingly deletes what came before. A shadowing follows and leaves its traces on film – a registration remains. It cannot be wiped nor recovered completely. It is someplace between being there and nothingness. It is the colour embedded within – a dull glow just beyond the surface. An echo of an image, it resonates to envelop the body in sight and sound.

The darkened chambers of photography – the camera and darkroom – are often absent when we look at photographs. It is what these architectures allow (a window to some other place) that negates their very presence. We suppress the action of looking through (the passage of light) to which their creation is owed. When uninhibited, light leaves its dark trace as margins on the photographic print. This shadow points directly to the parts that are otherwise missing, reinstating them to the viewing experience. It is this margin, this extra element (the absent presence of the camera/enlarger) that allows the whole image to be seen. In my work there is absolutely no cropping or subterfuge – nothing is secret or hidden in its display. What you see is what is. Despite appearances to the contrary, nothing could be more realist.

For a medium that in essence captures sight – that is, ‘seeing’ – so much of photography is navigated through blindness. This renders the process of taking a photograph and making a print heavily reliant on memory and touch. This is an intimate exchange between the film surface, the hand and the camera – of the body before it and inside it (as photographing like this is a task that requires an intense focus). I often close my eyes to imagine the marks being made, the order and sequence of events being transcribed. It is a form of mimicry – a repetition of every past photograph ever made. When I load the film, these hands that see, that touch, are outstretched and invisible, hidden inside a black bag. I fumble and fondle the sensitive surface of film to slip it into the dark slide – yet another darkened room for processes of transformation. I hide it with hidden hands. Photography is laden with actions and images inversed and multiplied, seen but more often unseen. It is a memoir of the blind.

It makes you wonder what it was like the first time, when a memory is made. Each time you revisit that memory, parts fall away (leaving just a few fixated details), like an ever-receding depth of field. Perhaps the Winter Garden photograph was like this for Barthes, as it was with Proust wandering through his childhood? When I think of Swann’s Way I think of staircases, the leaves on the trees, steeples and a mother. I think of a few details rather than the whole. All of which, when brought into focus, melt away at the edges. Barthes too is looking back through a scrim – the haze of plasma – at a picture that separates him from his own memories. His outstretched hand is forever reaching for a mother who is there, but not there. An outstretched hand forever reaching for that presence photography eternally promises but never quite delivers.