The Fragile Border by Kirsty Baker

… the fragile border … where identities (subject/object, etc) do not exist or only barely so – double, fuzzy, heterogeneous, animal, metamorphosed, altered, abject.[i] - Julia Kristeva

Convention leads us to believe that the photographic border delineates a fixed edge, a boundary by which the artwork is made separate from the world. We construct borders in order to separate, to contain, to rationalise, and to unify. Areola, at first glance, contains a profusion of borders. Blackened frames assert their static linearity over and over, hardened edges that contain unruly networks of enmeshed colour. Somewhat inevitably, this first glance misleads, for these are images that do their work slowly. Reading them is an intricate process of disentanglement.

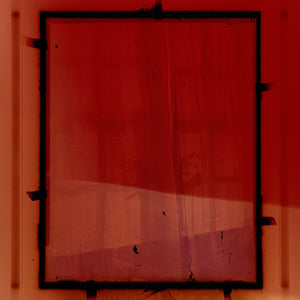

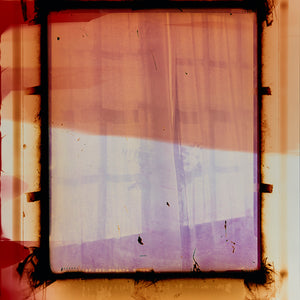

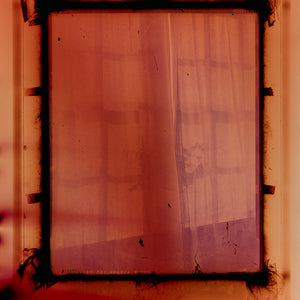

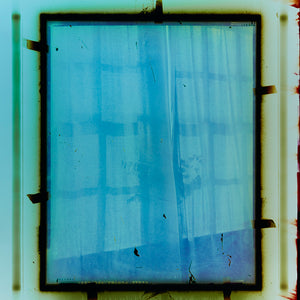

Here, a window.

Gauzy curtains, drawn together over a grid-like lattice, their undulations softening its industrial regularity. A sharp slice of brightness cuts through the image’s darkened interior. Falling off-centre it draws a shallow diagonal part way through the picture’s frame. The curtains – imperfectly closed – fail to contain this shard of light. In fact, the fabric is failing in its entirety. Rather than blocking light, it seems only to hinder its inevitable progression, altering the texture as it seeps pervasively onto the exposed negative. The fragility of the window as border, the curtain’s inability to block this light: it is these elements which allow a photograph to be made.

Here, then, a photograph of a window.

Such a reading assuages our spectatorial uncertainty. Allow the photograph to continue its work on you, however, and the inadequacy of such a reading becomes apparent. Notice now the darkened black rectangle surrounding the window: the regularity of its lines betraying the subtle tilt of the not-quite-centred image. Notice too, the burnished flare of luminescence radiating insistently outward. Uncontainable, it burns through the corners of the rectangular border.

As the curtains prove inadequate in the face of the light streaming through them, so too the framing mechanism of the enlarger – for that is what we see imposing its dark rectangularity upon the image – proves inadequate in the face of an overabundance of light.

Varga has referred to this effect as a ‘transgression of light’.[ii] Rather than policing such a transgression, she has embraced the visual and methodological complexity it brings to her work. The materiality of the printing process is articulated, rather than effaced. By choosing not to reign in the ‘imperfections’ of the image, Varga collapses multiple temporalities, locations and light sources into a single visual object. What we see here may be a photograph of a window, but it is one which occupies that fragile border space identified by Kristeva: it is ‘double, fuzzy, heterogeneous, animal, metamorphosed, altered, abject.’

Varga’s artistic practice demonstrates a sustained interrogation of what we assume photographs to be, and what we expect them to do. Utilising physical manipulations of the material surfaces she works with, Varga touches, smears and inverts negatives, she layers and overlaps exposures, she retains the visual residue of their processes of becoming.

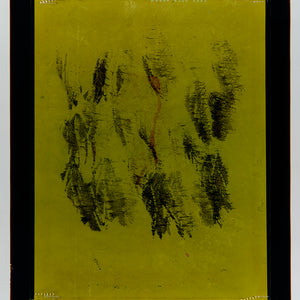

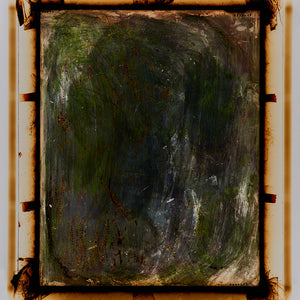

Etymologically speaking, the word areola has its roots in Latin, originally referring to a small, open space. Areola also refers to those ‘small spaces between lines or cracks on a leaf or an insect’s wing’.[iii] The pulsing network of fissures and interstices emerging from the photographic ground in Leafing #1, Leafing #2 and Leafing #3, gesture visually towards such a meaning. Made without a camera to act as intermediary, these images are manifestations of physical contact, visual traces of skin on skin. As she presses the pigment-smeared flesh of her hand onto the negative’s surface, Varga repudiates the lens’s definitive frame. Exploiting the tension between negative and positive, Varga’s tactile manipulations of her materials make evident the physicality of her process.

For here is an enlarged print of a positive-negative, alongside one made from its negative inversion. And, here, a composite of the two, their imperfectly aligned layers bringing forth a multitude of lines, cracks and spaces. Stripping the mechanistic reproductive power of the camera from the process of making a photographic object, Varga posits instead a method of bodily creation. The spatial and conceptual distance between maker and object is collapsed. Particles of skin and saliva mark the photographic skin, the body of the artist pervading the body of work. Stretching the picture’s frame beyond its conventional limits, these works complicate the certitude of the border which they both occupy and expand.

Today, of course, the areola is most commonly associated with the coloured ring of flesh between nipple and breast. Here, again, we are confronted with an expanded border-space, an encompassing series of creases and undulations encircling the point at which fluid can be expelled from the human body. The skin of the photograph is as mutable as that of the body, both continually inscribed and re-inscribed with meaning. Exhibiting fragility and permeability, the borders in Areola fail to contain: colours seep, light bleeds. The images transgress.

Straining against the limits of the photograph, these images occupy and expand the border space. The harsh delineation of the pictorial frame is transformed, becoming an elastic space of indeterminacy, an expansive in-between. In a contemporary climate where the socio-political discourse concerning border spaces is freighted with toxicity, there is something subversive about Varga’s refusal to grant the border its limiting power.

Near the beginning of Kristeva’s Powers of Horror, she identifies death, or more specifically the corpse, as ‘a border that has encroached upon everything’.[iv] If, as many after Barthes would argue, all photographs are ultimately about death, then all photographs are marked by the encroaching finality of such a border. In Areola, Varga’s works hang suspended within an expanded border space: a space between subject and object, photograph and world, negative and positive, within and without. Rather than being encroached upon, Varga’s transgressions of light dematerialise the photographic border, in order to proclaim their own, altered life.

Kirsty Baker is a writer living in Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand, where she is a doctoral candidate in Art History.

[i] Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982) 207.

[ii] Justine Varga, in conversation with the author, 5 January 2019

[iii] Oxford English Dictionary, https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/areola accessed 10 January 2019

[iv] Kristeva, 3.