'Justine Varga: Sounding Silence' by Isobel Parker Philip

In Justine Varga’s photographs, legibility and abstraction coalesce. Her subjects are shy, slipping in and out of visibility. Even those recognisable forms that creep into her work remain guarded. Varga deifies quiet gestures and unassuming objects; a shard of light clinging to a piece of sticky tape on a bare white wall, a crumpled piece of paper. Her compositions flirt with the absent and empty. Still life scenes assembled out of mundane objects are transformed into restrained studies of form and light.

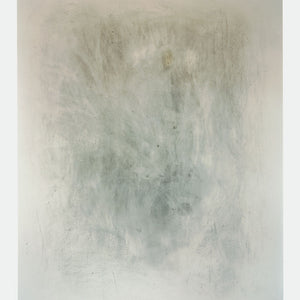

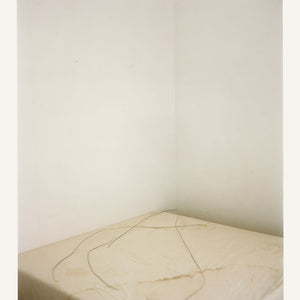

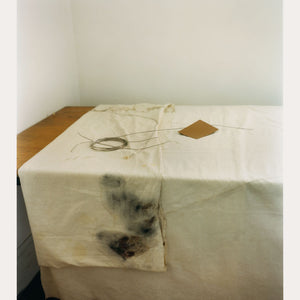

In Sounding Silence Varga continues to explore the humble landscape of her studio. Both a backdrop and a subject, the studio that appears in this suite of photographs is not the same space that was memorialised in her 2012 series Moving Out yet the two are almost interchangeable. Both rooms are nondescript and anonymous. Pared back and denied any architectural idiosyncrasy, they become her blank canvases. An artist studio is a mutable and performative space. It is a site of generative potential, a naked space waiting to be dressed. An any-space. Even so, the studio in Sounding Silence functions very differently to the one in Moving Out. In Moving Out the contours of Varga’s studio are transformed into a geometric plane intercepted by circles and diagonal lines made out of wire suspended against bare walls. Corners become two-dimensional linear compositions and slabs of light hover like iridescent rectangles. In Sounding Silence the choreography is different. The objects don’t hold their poses in the same way, for their rigid composure has been offset. Wire no longer levitates but lies collapsed on a table while tax receipts remain crumpled and comatose. Form relaxes like a slowly exhaled breath.

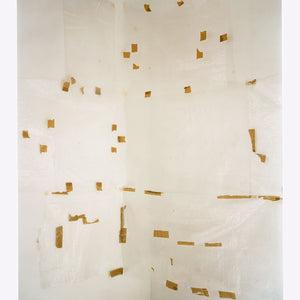

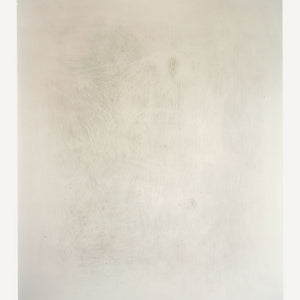

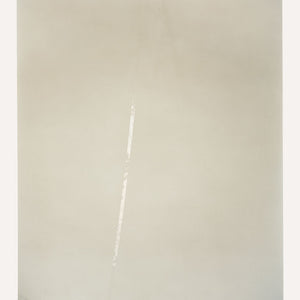

These still life scenes and spatial interventions are scaffolds. Here, surface is venerated above all else. Each photograph is a portrait of ephemeral textures and semi-perceptible membranes. There are the sheets of pre-used bubble wrap pockmarked by scraps of masking tape and the translucent plastic drop sheet. The light that dances across these surfaces becomes another membrane draped over each photograph. There is also the partially erased wall drawing. Reduced to a faint trace of charcoal, this drawing is nothing more than a textual memory.

Varga’s preoccupation with texture and surface defines the topographic limits of each image. We aren’t invited to penetrate or inhabit these spaces; we linger in the shallow end as depth is perverted. In Sounding Silence #1 the bubble wrap partition creates a false corner at odds with the contours of the room itself. The gap between the table and the wall in Sounding Silence #7 performs a similar feat. The shadows that seep out of this narrow precipice subtly confuse the spatial logic of the scene.

This spatial compression is exaggerated by the gentle modulation of each photograph’s shallow depth of field. Our eyes are pulled across the images rather than into them. We follow as the photographs dip in and out of focus. En route we stumble upon tiny surface aberrations. These specks of dust, souvenirs from the analogue photographic process that have been left undisturbed, provide an additional textural dimension. Faint tributes to the phenomenon of photographic inscription, these marks appear like a porous skin stretched over the image. The flat surface of the photographic negative collides with the three-dimensional space of the room.

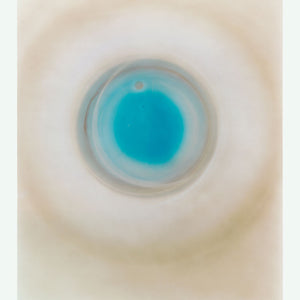

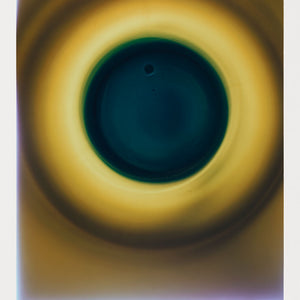

What these specks tentatively reveal — namely the material specificity of the photographic surface — is overtly elucidated in the pair of camera-less photographs included in the exhibition. Morning and Evening are inverse images of the same photographic event. A tea light was placed directly on top of two 4×5 film negatives. When Varga struck a match to light the candle, each film was exposed. Relinquishing the camera, Varga worked directly onto the photographic surface.

In these two images the photographic event is not defined by the speed of the camera’s shutter but by an external force. The act of lighting the match becomes a pseudo-photographic gesture, a fact that acquires metaphoric resonance in relation to each work’s title. Heralding the ‘morning’ and ‘evening’ respectively, the orbs in these photographs become Suns. One rising, the other setting. As portraits of an external force much like the match used to light the candle, these abstract photographs are disguised landscapes.

The concentric circles that emanate from the centre of each image are windows or portals into an undefined exterior space. They demarcate an expansive and impenetrable ‘outside’ against the closed interior world of the studio.

Metaphoric thresholds between interior and exterior space, the floating orbs in Morning and Evening are spatial agents but they are also temporal markers. They are diurnal bookends that signal the transition from day to night and back again. The photographic equivalent of a parenthesis, they delineate a cyclical pocket of time that becomes the temporal framework on which the rest of the exhibition turns. To situate Varga’s photographs within this interval we must negotiate the spatial boundaries that separate day and night. Writing in 1963, German philosopher Otto Friedrich Bollnow discusses the distinction between day space and night space.i Where day space is defined and mediated by vision, night space denies the eyes their sovereignty and privileges tactile and sonic perception. We feel and hear the night.

While Varga’s photographs do not abandon light or the eye — how can they? — they somehow manage to appropriate the spatial sensibility of the night. In its obsession with surface and texture, her work courts a detached tactility. We cannot physically touch her photographs but we engage with the ephemeral and membrane-like textures they depict. We caress them from a distance. In this sense Varga’s work straddles day space and night space. It is fitting, then, that the scenes she unveils correspond so perfectly with Bollnow’s description of twilight as a state of ‘semi-clarity… (in which) individual objects lose their sharp contours and dissolve into a medium that flows through everything.’ii

In Varga’s photographs boundaries melt. Object and empty space absorb one another, entwined within self-contained compositional studies. Twilight, as Bollnow maintains, creates spatial intimacy.iii Distances contract and depth is subverted. The same phenomenon occurs in Varga’s work. Her spaces are nothing if not intimate.

This incongruous metaphor (in which the term ‘twilight’ is associated with photographs that were shot almost exclusively in daylight) resonates despite its apparent illogicality. Twilight is state of transience and transcendence. Day slips into night, darkness encroaches and space transforms. Like the artist studio, Varga’s loyal subject, twilight is mutable and performative.

In describing Varga’s photographs as twilight images — images of transience and transcendence — we acknowledge her ability to traverse boundaries. We honour her capacity to cultivate darkness through light, form through absence and sound, the hero of nocturnal sense perception, through silence.

–

i[1] Bollnow, Otto Friedrich (trans. Christine Shuttleworth). 2011. Human Space. London: Hyphen Press pp. 201-2115

ii[1] Ibid p. 206

iii[1] Ibid pp. 210-111